P A G E 1 3

V O L . 4 , N O . 1

J U L Y 2 0 1 5

from 38 g (juveniles) to 69 g (adult female with a fat tail) and fitted descriptions of both species when coat color and

general size was taken into consideration. Overall, Marojejy individuals were larger in size than Anjanaharibe Sud

mouse lemurs, so we could, in principle, say M. macarthurii may be present in the former and M. mittermeieri in the

latter, but that is a barely-educated guess at this point, without having the genetic information. Personally, I found it

intriguing that mouse lemurs at the Marojejy low elevation site were ready to mate again in early April (the first estrus

in females generally occur in September or October depending on species and sites) as evidenced by a vaginal opening

and a vaginal swelling of captured females (vagina remains sealed except during the short estrous periods) but adult

mouse lemurs in Anjanaharibe Sud were showing evidence of tail fattening in anticipation of periods of prolonged tor-

por. Thus, at least some individuals at Anjanaharibe Sud cut reproductive season short and remain inactive most of the

winter season relying on stored fat. These are just examples of a variety of strategies mouse lemurs can display under

different environmental conditions, and that’s why they hold the title of most “ecologically flexible” lemurs out there.

For anybody interested in the genetic results of these expeditions, however, I’ll be giving updates as soon as samples

are analyzed.

Whose Mouse Lemur Is It?

Continued

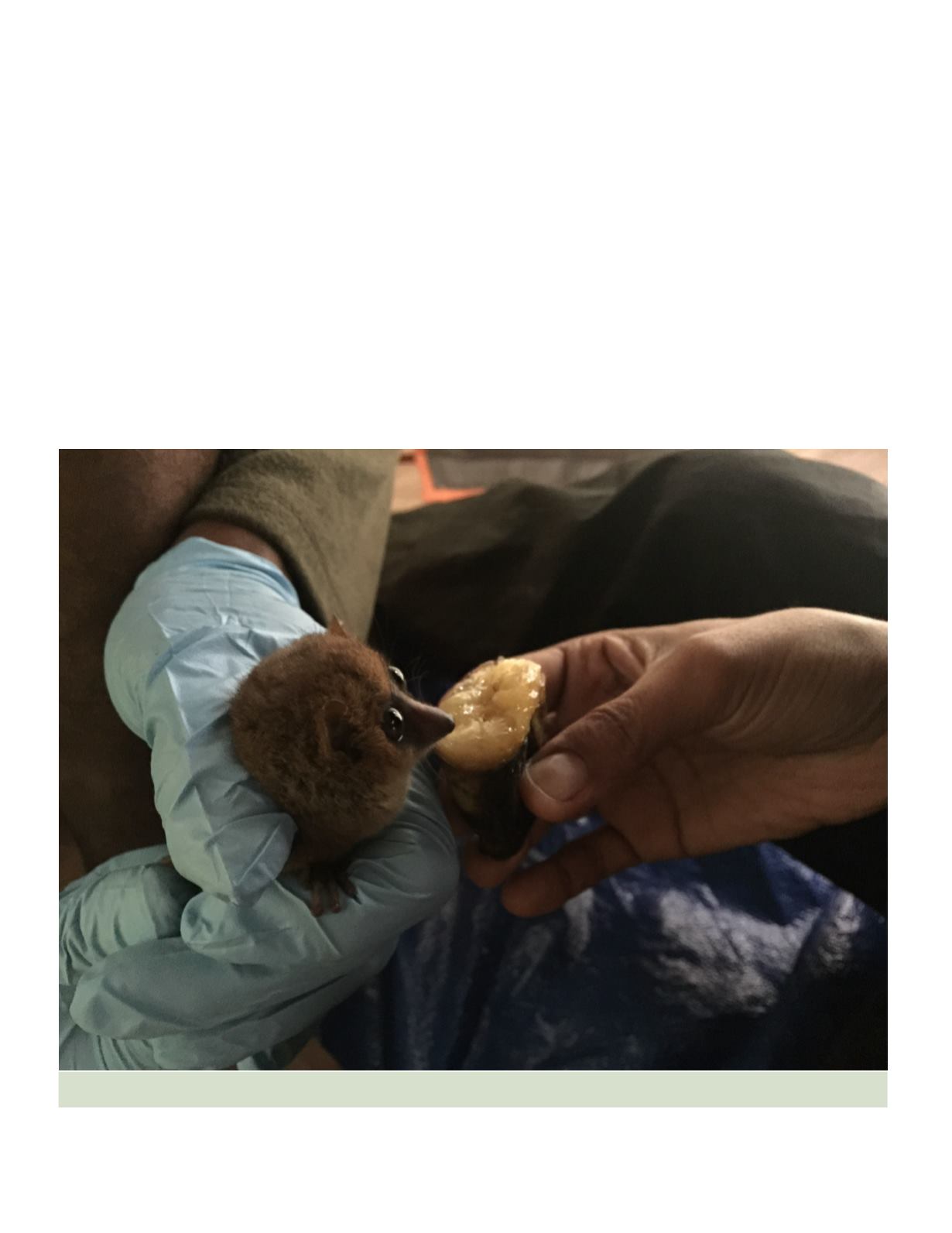

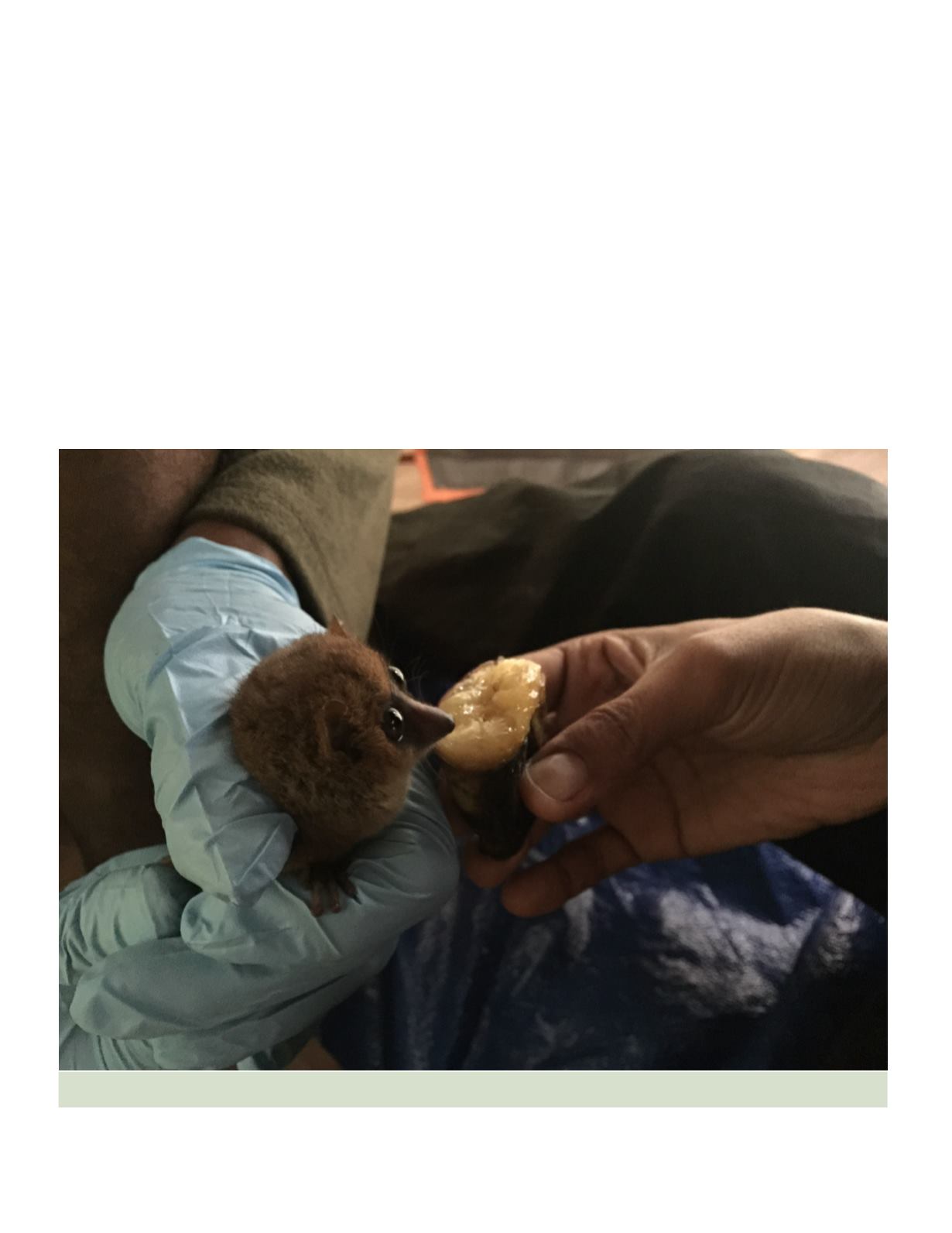

A banana snack reward after putting up with data collection.